Life

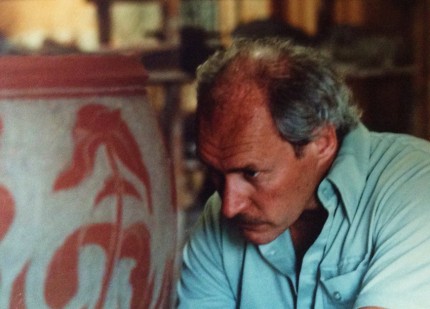

Melvin Jay Lindsay (June 14, 1943 – September 27, 2015) was a New York-based American artist, master potter, ceramicist, teacher, sculptor, painter and adventurer. Jay Lindsay is best known for his large-scale pottery, figurative bronzes, world travels, and sculptural work for Tallix Art Foundry, Beacon, New York.

Early Years

Born in Eugene, Oregon to Curtis Allen Lindsay (1917-1994) and Zelma Alice Dickson (1921-2008), Melvin Jay Lindsay was the first of four children. He was named after a friend of his parents but never particularly cared for the name Melvin. He much preferred simply ‘Jay.’

Born in Eugene, Oregon to Curtis Allen Lindsay (1917-1994) and Zelma Alice Dickson (1921-2008), Melvin Jay Lindsay was the first of four children. He was named after a friend of his parents but never particularly cared for the name Melvin. He much preferred simply ‘Jay.’

A World War II baby, Jay first met his father when Curtis proudly returned in October 1945 from his voluntary enlistment in the Pacific Theatre as a Fighting Seabee, (US Naval Construction Battalion). He wondered who this man was, insinuating himself into their small family. As time went on, he became very close with his father and enjoyed being the only child. Until he was seven, when his sister Roxanne — and the 1950s — were born. The family grew larger, his parents grew older, and more conservative.

Lindsay’s father and grandfather before him were builders specializing in heavy construction, bridges and roads. Grandfather Fred Hoopes Lindsay’s firm, Rocky Mountain Construction, was responsible in part for the construction of the scenic Beartooth Highway, a 68-mile byway which winds through southwest Montana and northwest Wyoming, leading into Yellowstone National Park at its Northeast entrance. Lindsay’s father Curtis worked on this and many other projects for the firm, eventually studying engineering. By the 1950s, Curtis sold his small business, and went to work for a larger firm. It provided the more stable income he needed for his growing family.

Jay Lindsay first worked for an upholsterer, and then construction jobs during the summers for Wildish Construction (founded by a cousin of his grandfather). The experience helped to define his analytical and engineering skills he’d later use when planning the construction of large-scale bronzes. But it was hard, dangerous work. When an uncle died on a job site, Jay was very deeply affected. His father cautioned, ‘maybe this isn’t the job for you.’

Jay knew from a very early age that he wanted break free from that family tradition and be an artist…

“At sixteen I choose a life as a artist because of it’s reflective and creative nature, and a need to express my spirit. When you have a work of art, it is not just an object, it is part of the flame that is the artist’s spirit.”

Education

Jay Lindsay with his mother, Zelma, 1948.

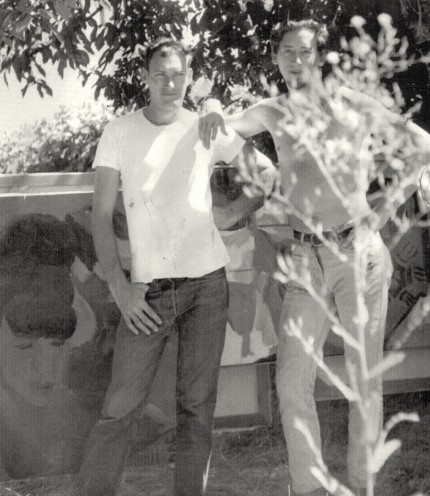

With artist Tom Blodgett in 1964. They met at University of Oregon and became life-long friends.

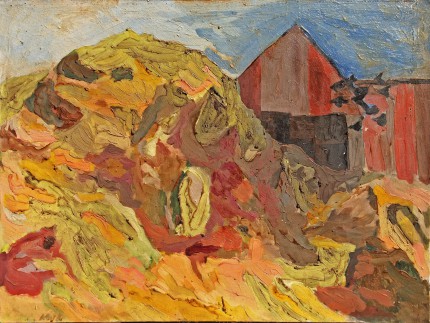

There he met fellow student Darya Zoe Tucker, daughter of architect Stanley Verdell Tucker (1916-2002) and Relta Lea Powell (1917-2009). They were married in her hometown of Milton-Freewater in 1964. They rented a small house on Washington Street in Eugene, a mile west from the UO campus, where he set up a studio to paint and draw. His paintings from this period were oils, impressionistic interpretations of the Oregon outdoors he so loved.

Lindsay earned a BS degree from University of Oregon in 1966. Just weeks later, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. Before leaving for Fort Lewis, Jay and friend Tom Blodgett traveled. He often reflected on the times they had in Sulphur, Nevada, drawing and painting.

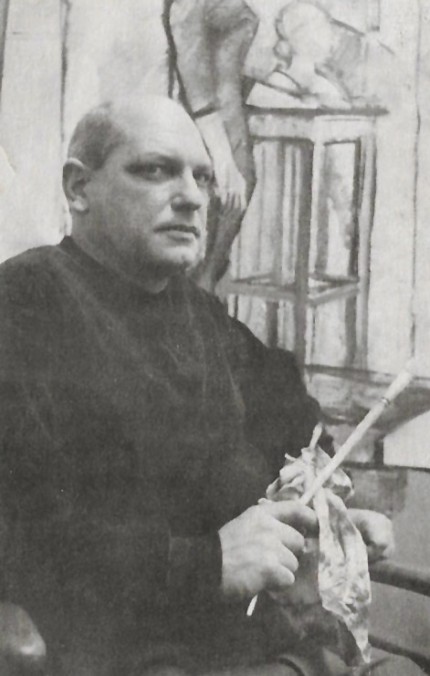

Painter Jack Wilkinson, 1957

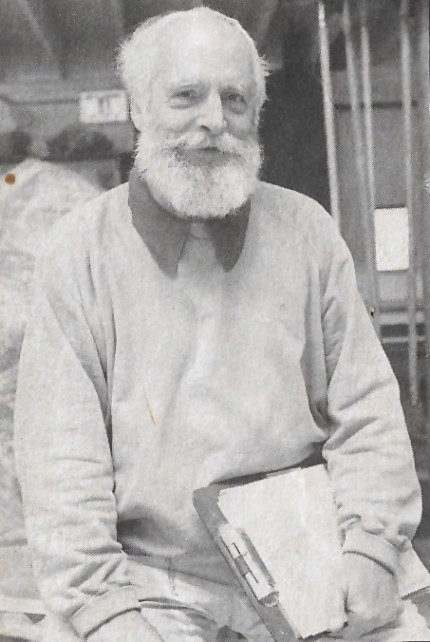

Ceramicist Bob James

The Artist During Wartime

“I’ve been aptly described as ‘fiercely independent,’ but it allows a different perspective on things. Not superior or inferior, but different. I’ve never thought that you become more insightful with age, more experienced of course, but only .01% of experience increases knowledge, the rest merely clutters the mind with the daily bric-a-brac of life, the older you are the worse it becomes. I made some long-term decisions when I was 16 and probably long before that.”

As an indication of his willingness to serve, Jay declined to apply for a 1-0 classification, which, if granted, could have provided for his immediate honorable discharge. So Jay was sent to Fort Lewis, Washington for bootcamp. Army life did not agree with the ‘fiercely independent’ artist. Certainly not the brutal de-humanization of basic training, nor the prospect of being shipped off to Vietnam to kill ‘total strangers.’ The trainees had a two-week leave for Christmas, during which Jay concluded that he ‘could not participate in any program whose purpose was to train him to kill’ and that his personal morals would lead him to resist. His father disagreed, and couldn’t understand why Jay refused to ‘fight for his country’ as he had twenty years before. Jay applied for status as a non-combatant (classification 1-A0) on the grounds of conscientious objection, which was turned down. During bayonet practice, trainees were required to stab at dummies while yelling, ‘KILL!’ Once he made his decision, Jay refused to check out a rifle and bayonet, and was immediately arrested.

“My battalion commander threatened, ‘If this was a declared war, I would put you against a wall and have you shot!’ I told him to go ahead. If you protest, it is with your life.”

On June 26, 1967 Jay Lindsay was court-martialed for disobeying a direct order. He was found guilty, demoted to the lowest rank possible, forfeited all pay coming to him, and sentenced to a dishonorable discharge and three years hard-labor at the United States Disciplinary Barracks in Leavenworth, Kansas. His defense as a conscientious objector was disallowed, as the Army’s law officer explained, ‘an order which may be against a person’s moral or religious feelings is still an order and his feelings are not a defense. We are not here to determine if private Lindsay is a conscientious objector.’ The military at that time was making an example of conscientious objectors as a deterrent to the youth of America’s growing discontent with the Vietnam War. ‘Throwing the book at us.’

“I figured that since wasn’t really a criminal, it would probably be the only time I would be in that unique situation. Leavenworth was built after the civil war as a castle, and has a dark very, Gothic feel to it. The turn-keys were mostly shell-shocked Korean War veterans, which added to the ambience. Of course, it was very violent and loud as well. Three were murdered while I was there…”

During his time at the USDB, he drew and painted with what little art supplies he could scrounge or afford. He started an art class and worked on the in-house publication, Hot Shots, eventually becoming its editor. Little or none of Jay’s works from this period survive, they were destroyed. Jay tried sending some drawings and paintings to his wife, but they were intercepted. Leavenworth officials considered further punishing Jay — although he’d used his own paints, the paper they were painted upon they contended, was the prison’s and he was, in effect, ‘stealing US Government property.’ He later surmised that this was in retribution of Darya’s letters to the commanding officer in which she described him as ‘the most belligerent, arrogant person she had ever met.’ At one point the entire magazine’s staff was punished with solitary confinement, (one of the men was forging IDs with presstype, and no one would give him up). Through the aid of civil rights attorney William Hanson, Jay’s sentence was eventually overturned and he was released. He spent the remainder of his tour of duty in Saint Louis and was honorably discharged with full pay in November 1968.

New York

On his return from military service, Jay sought advice from his college mentor Jack Wilkinson, then Fine and Applied Arts Department head. Wilkinson told him to ‘move to New York and do your artwork and never come back!’ It seemed like a great idea to Jay and Darya to get out of Eugene — as time went on there was less and less to keep them there. After his return, Jay’s relationship with his father became very strained. Curtis felt Jay had dishonored the family for not serving, and muttered about ‘disowning’ his son. His mother was much more supportive, but still wanted him ‘to get a real job.’ Everyone in his family was scattering. Sister Roxanne moved to college dorms. In late 1969, his father, mother and two younger brothers moved to Southern California.

That same year Jay entered the wilds of New York to make his way as an artist, settling in a small house in Holmes. Three years later, he and his wife had a daughter, Zoe. Their marriage lasted another four years.

That same year Jay entered the wilds of New York to make his way as an artist, settling in a small house in Holmes. Three years later, he and his wife had a daughter, Zoe. Their marriage lasted another four years.

“The ’50s American dream of unlimited possessions to me was the American nightmare, never having the desire to own anything, or at least only the minimum. Possessions, entrap one into earning money and demand constant maintenance and time-consuming thought. It is a fortress most build to convince themselves that they are ‘important and protected,’ not merely a speck in the fabric of space and time. The fortress grows larger with drawers of unworn clothes and garages and attics of useless junk, only to have a yard sale and immediately buy more, and extend it to owning their kids, wives, husbands…”

After their divorce, Jay moved to a studio on Moss Hill Farms, the estate of his cousin Erik Johns, in the Hudson River Valley. Born Horace Eugene Johnston (1927-2001), he changed his name to Erik Johns to pursue his own artistic career as a modern dancer in New York. Johns had worked with composer Aaron Copland on the operetta The Tender Land. And with Jack Kelly in the 1950s, Johns formed Johns and Kelly, a design company that decorated inaugural balls for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter. Erik’s love of travel, beliefs in Eastern religions, mysticism, meditation and the pure enjoyment of life were impactful on his younger cousin Jay.

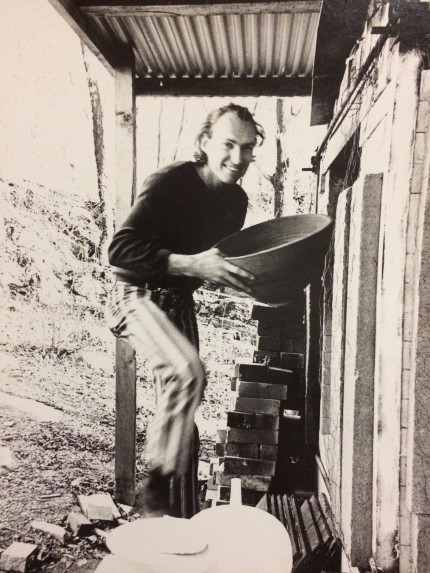

Literally a cabin in the woods, Jay’s Moss Hill studio would become the center of his creative output for decades. He quipped that the nearby forest trees were growing up and old with him. Little more than a one-room shack with holes in the floor and masking taped windows to keep out the cold winters, the studio was all he needed. He designed and built his own potting studio complete with sprung-arch gas-fired, high temperature kiln. Later, he added a custom superstructure for pouring small bronzes. With fellow artists from Tallix was constructed a rock and earthen topped wine cellar, to age their yearly batches of Vino Bingo wines made with grapes purchased in the city.

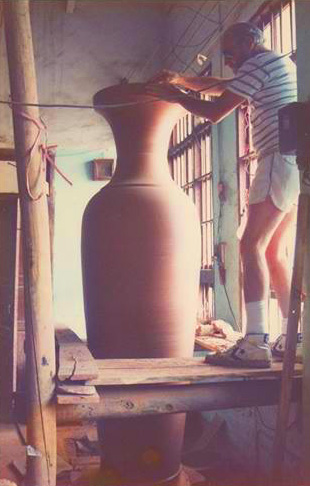

In New York, he established his reputation as a master potter who threw large pieces — planters, plates, lamps — most often in the forms, textures and images from his travels. It was often a normal sight to see him throwing 100 pounds of clay into one pot, and at point in his career, he was going through eight tons of clay a year. He exhibited his work in national craft fairs, shows, galleries in New York City and throughout the country. His work is in the collection of Museum of Contemporary Crafts, among others.

Jay was director of the Garrison Art Center from 1970-1985, where he established community art classes and group exhibitions. In 1984, his work and methods were prominently featured in Glenn Nelson’s seminal textbook, Ceramics: A Potter’s Handbook.

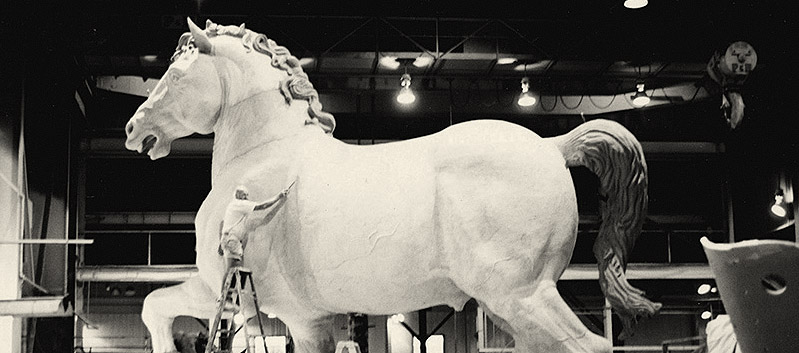

During his employment as sculptor at Tallix Art Foundry in Beacon, NY, from 1985-2002, he worked on the 24-ft tall bronze Leonardo Da Vinci horse statue, Il Cavallo, now in Cultural Park, Milan, Italy, and with many renowned artists who could rely on him to cast their work as they had conceived it. Trusting him as a fellow artist, they often followed his suggestions to resolve casting problems to improve the final pieces.

In 2006, Lindsay taught ceramics and held workshops on kiln building at the Art Student League’s Vytlacil Campus in Sparkill, New York.

Travel

With just thirty percent of his heart’s function remaining after major heart surgery in 2002, Jay retired from Tallix, but continued to test himself with adventurous treks that would discourage those half his age and with healthy hearts. His surgery was just another obstacle to from which to recover — and surpass.

He was especially drawn to the desert and made many trips to Baja California: to the canyonlands of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah; to Joshua Tree, Anza-Borrego and Death Valley, California; and to the sagebrush and canyon country of his native Oregon that sparked a kinship with these arid landscapes, vibrant with plants and animals that survive — and thrive — in the harshest conditions.

“Most fear death as though life is a possession. It’s merely a vehicle you ride in for a short while. So what — if life has it’s share of suffering, pain, failure, struggle. They’re part of the warp of the tapestry, as much as play, happiness and contentment. It’s like someone saying, ‘I like red and blue, but I can’t stand green.’ All the colors are important. People say ‘I want to be happy.’ All the time? How boring and limited. I crave the whole meal. To have insight, you need to be a part of — and apart from — the thing. It is of equal importance.”

In his last few years, he traveled to Africa twice, camping for six weeks at a time. Twice he hiked into the humid jungles of the Amazon to visit the remote Yanomami and other tribes with a guide who killed what they ate along the way. Sketches and watercolors from these and numerous other trips in places across the planet — Australia, China, Morocco, Costa Rica, France, Greece, India, Patagonia and in 2014, Japan — inspired his well-known ceramics and sculpture today found in many public and private collections.

Lindsay died on September 27, 2015 in Carmel, New York of complications from heart failure. He was 72.

Those who knew him remembered Jay Lindsay as a gentle, generous and adventurous man, instilled to the bone with an unyielding will to live his life and his art to the fullest, even — and especially — when most challenged. We may take heart from his extraordinary life, and the multitude of evocative drawings, watercolors, pots and sculpture that embody his singular vision and adventurous spirit.

“People have said to me on numerous occasions, ‘Jay, you are not in the real world.’ Why would I want to be? It so limiting, like being bound in a straight jacket. I would much rather be a lark in the sky, or a potter…”

“M. Jay Lindsay: His Life”

by Martin S. Lindsay

San Diego, 2015